Who Are the Fungi?

Fig: Beautiful pink Fusarium repeatedly isolated from mycangia of Xylosandrus crassiusculus. Is it the actual nutritional mutualist? As with many of these mycangial fungi - no one knows. Photo J.H.

Ambrosia fungi

Just like the term ambrosia beetles, the term ambrosia fungi does not refer to a monophyletic group of fungi. There are a number of fungal clades that were adopted by the beetles during the evolution of their xylo-mycetophagy as nutritional symbionts. Most of commonly reported and confirmed nutritional mutualists of ambrosia beetles are polymorphic asexual anamorphs from the genera Ambrosiella, Raffaelea, Ambrosiozyma (strange filamenotus yeasts), and Dryadomyces (polyphyletic, Ophiostomatales and Microascales), occasionally Fusarium (Hypocreales). The most comprehensive phylogeny showing multiple origins of the ambrosia ecology in different fungi is by Sepideh Alamouti et al. (2009).

That is what is known about temperate ambrosia systems. The composition of ambrosia communities in the tropics may be quite different. The first few explorations of tropical ambrosia systems yielded not only the expectable Ambrosiella and Raffaelea, but also highly evolved ambrosial Geosmithia (M. Kolarik, in press.), bunch of unidentifiable Ceratocystis-like strains (Hulcr & Cognato,2010), or even Gondwanamyces (Hulcr et al., 2007).

There are three basic features that define ambrosia fungi:

- there are mechanisms assuring that the fungi remain predominant associates of a given ambrosia beetle, transmitted horizontally between generations in mycangia,

- the fungi are polymorphic, producing filaments in the wood and a yeast-like morphology (or “monilioid” stage) in mycangia, and

- the fungi provide nutrition to the beetles.

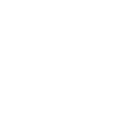

Fig: Polymorphism of an ambrosia fungus Ambrosiella hartigi associated with Xylosandrus germanus. A) yeast-like phase inside the beetle mycangium, b) filamentous stage in wood or on agar media, c) palisade mycelium on the surface of the gallery (that's what the beetles graze on. Photos J.H.

There are significant question marks around all these features, especially the first one, since the mechanisms of fungus-beetle specificity are a complete mystery.

Originally it was thought that two other features define an ambrosia fungus – the fact that it is not capable of living independently of the beetles, and that they are asexual anamorphs only. Although majority of the traditionally recognized ambrosia fungi fit these definitions, many significant nutritional symbionts may not (for example, Fusarium or Geosmithia (M. Kolarik, in prep.)).

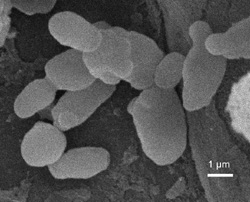

Fig: Abundance of yeasts in the larval chamber of Dendroctonus frontalis, whose larvae display ambrosial habit. The identity and function of the yeasts is unknown. Photo J.H.

Ambrosia yeasts?

The yeasts in ambrosia beetle galleries have often been the elephant in the room. Every comprehensive study of the ambrosia fungi community always reports and abundance of yeasts (Ganter, 2006). In my own experience, yeasts are some of the most abundant organisms inside ambrosia beetle mycangia (the pockets used for fungus transport). However, to my knowledge, no study has ever been done on their function in the ambrosia symbiosis. The pattern emerging from many incidental studies suggests, that yeasts are omnipresent in the environment that scolytine beetles create, but any evolutionarily stable feedback from the yeasts to the beetles is hypothetical at best.

There is one exception to the uncertainty about the role of yeasts in ambrosia beetle life history. Non-scolytine ambrosia beetles from the family Lymexylidae, or ship-worm beetles, practice “yeast agriculture”. Just like regular ambrosia beetles, they bore tunnels in dead trees and rely on fungal symbionts for nutrient provisioning, except in the lymexylid symbiosis, the fungal partners are yeasts from the genus Ascoidea.

References

Alamouti, S.M., Tsui, C.K.M., & Breuil, C. (2009) Multigene phylogeny of filamentous ambrosia fungi associated with ambrosia and bark beetles. Mycological research, 113, 822-835.

Ganter, P.F. (2006). Biodiversity and Ecophysiology of Yeasts. In The Yeast Handbook, pp. 303-370. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg.

Hulcr, J., Kolarik, M., & Kirkendall, L.R. (2007) A new record of fungus-beetle symbiosis in Scolytodes bark beetles (Scolytinae, Curculionidae, Coleoptera). Symbiosis, 43, 151-159.

Hulcr, J. & Cognato, A.I. (2010) Repeated evolution of crop theft in fungus-farming ambrosia beetles. Evolution, 64, 3205-3212.