Ambrosia Beetle Ecology

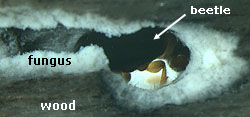

Fig: Ambrosia fungus inside the gallery of an ambrosia beetle (Xylosandrus compactus). Photo J.H.

Ambrosia beetles are a group of unrelated scolytine weevil clades defined by a shared ecological strategy: fungus farming. Most bark and ambrosia beetles (the two weevil subfamilies Scolytinae and Platypodinae) are somehow associated with fungi. The relationship varies from association with phytopathogens, through enrichment of herbivorous diet with fungal mycelia, to strict mycetophagy. Ambrosia beetles are the vaguely defined end of this spectrum, the beetles which, instead of eating tree tissues as their ancestors, carry around symbiotic fungi, inoculate them into the trees they colonize, and are dependent on fungi as their main source of food.

There is no explicit definition of “ambrosia beetle,” but the following criteria are often used: 1) fungi represent the main source of the food consumed by ambrosia beetle larvae and adults, 2) the fungal symbiont or symbionts are non-random associates, transmitted by the beetles from one host to another and between generations, 3) the beetles are not able to survive and develop on a fungus-free diet composed only of plant tissue. A direct consequence of condition (1) is that larvae do not form their own feeding tunnels, although they may substantially participate in excavating a common breeding chamber or their own larval cradles. We do not consider strict feeding on fungi and the possession of mycangia to be defining characters of the symbiosis, since many exceptions exist.

Unlimited host range

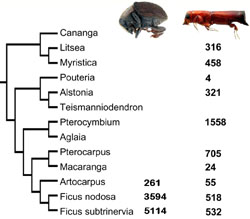

Fig: Example of a restricted host range of a regular bark beetle (left, Diamerus), and an unrestricted host range of ambrosia beetles (right, Dinoplatypus). The beetles were reared from trees representing a wide diversity of vegetation in lowland rainforests in New Guinea. From Hulcr et al. (2007b).

Deploying mycelia of symbiotic fungi as means of extracting nutrients from trees freed ambrosia beetles from facing the defense mechanisms of trees. As a result, host tree range of some ambrosia beetles seem nearly unlimited. Hulcr, Cognato and colleagues from Papua New Guinea reared ambrosia beetles from a wide variety of rainforest trees, thereby testing factors that may govern ambrosia beetle species selection – the phylogenetic identity of trees, wood density, and water content. Surprisingly, we found out that with sufficient sampling one can rear most ambrosia beetles from almost any species of tree (Hulcr et al., 2007d).

There are a number of ambrosia beetle species or whole groups that display restricted host choice, but it usually has a biogeographic twist. For example, Xyleborus glabratus is exclusively found in Lauraceae in North America where it is an invasive species, but no such specificity was reported from its native SE Asia. Euwallacea fornicatus, on the other hand, seems to be mostly interested in Artocarpus in Asia, but no such specificity in the invaded regions of USA and Israel. There are many genera specialized on Dipterocarpaceae or Fagaceae, for example Webbia or Cryptoxyleborus from Xyleborini, or Genyocerus from Platypodinae (Beaver & Liu, 2007). Camptocerus species (Scolytini) are specialized to Protium species in the Neotropics. Even more host-specific are the few ambrosia beetle species that attack live trees. For example, Austroplatypus incompertus, an eusocial platypodine, colonizes only live Eucalyptus trees (Smith et al., 2009). Xyleborus vochysiaecan is found in live Vochysia sp. in Costa Rica, and nowhere else (Kirkendall, 2006).

Huge geographic distribution

The expanded host tree range, combined with an amazing capacity for dispersal by flight, allowed some ambrosia beetles to colonize enormous geographic ranges. This can be seen in two ways — some species of ambrosia beetles belong to the most widespread insect species on Earth. For example, Xyleborus affinis, Xyleborus perforans, and Xylosandrus compactus can be found in all regions with tropical vegetation, including islands as remote as New Caledonia or Hawaii. (Cognato & Rubinoff, 2008, Hulcr & Mille, unpubl.). This capacity also makes ambrosia beetles some of the most invasive insects.

Evolutionary and ecological success

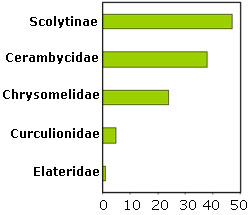

Fig: The dominance of ambrosia beetles (labeled as Scolytinae, which were mostly represented by ambrosia beetles) among beetles reared from various parts of Ficus nodosa. (data from the database of the Binatang Center in New Guinea).

There are about 3,200 described species of ambrosia beetles. That’s more than in any of the other fungus-growing insect groups. Moreover, some ambrosia beetles are still diversifying unusually fast. The beetles are also a dominant component of the beetle fauna of tropical forests. In the picture on the right there is an overview of the community of beetles reared from one species of Ficus in Papua New Guinea. Even if you include beetles chewing leaves or boring into roots, ambrosia beetles are still the most speciose group of beetles. More about the ambrosia beetle diversity is in the Diversity section.

Low beta diversity

The other evidence for huge geographic ranges is the lack of beta diversity, or species turnover, in communities of tropical ambrosia beetles. Hulcr, Cognato and colleagues sampled the ambrosia beetle community on a 1000 km transect in Papua New Guinea, and found no statistically significant change along this distance (Fig. on the right; Hulcr et al., 2007c). At each locality, we nearly exhausted the local fauna, so even though some rare species may have limited distributions, most of the ambrosia beetles can be found simply everywhere throughout a contiguous rainforest. There is another measure of beta diversity — the proportion of regional fauna that can be intercepted at a single locality – and even that is unusually high in ambrosia beetles. For example, several avid bark and ambrosia beetle researchers (Roberts, Gray, Wyllie and Shanagan) spent portions of their careers in a middle-elevation research station in Bulolo, Papua New Guinea. Their combined collections intercepted 47% of Xyleborini species known from the whole island, from sea shores and mountain ranges! Even more – 54% – of total species from New Guinea were collected during our collecting and rearing program in Ohu and Wannang villages (also New Guinea) between 2002 and 2006.

References

Beaver, R.A. & Liu, L.Y. (2007) A review of the genus Genyocerus Motschulsky (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Platypodinae), with new synonyms and keys to species. Zootaxa, 1576, 25-56.

Cognato, A.I. & Rubinoff, D. (2008) New exotic ambrosia beetles found in Hawaii (Curculionidae: Scolytinae: Xyleborina). Coleopterists Bulletin, 62, 421-424.

Hulcr, J., Kolarik, M., & Kirkendall, L.R. (2007a) A new record of fungus-beetle symbiosis in Scolytodes bark beetles (Scolytinae, Curculionidae, Coleoptera). Symbiosis, 43, 151-159.

Hulcr, J., Mogia, M., Isua, B., & Novotny, V. (2007d) Host specificity of ambrosia and bark beetles (Col., Curculionidae: Scolytinae and Platypodinae) in a New Guinea rain forest. Ecological Entomology, 32, 762-772.

Hulcr, J., Novotny, V., Maurer, B.A., & Cognato, A. (2007c) Low beta diversity of ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae and Platypodinae) in lowland rainforests of Papua New Guinea. Oikos, 117, 214-222.

Kirkendall, L.R. (1983) The evolution of mating systems in bark and ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Scolytidae and Platypodidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 77, 293-352.

Kirkendall, L.R. (2006) A New Host-Specific, Xyleborus vochysiae (Curculionidae: Scolytinae), from Central America Breeding in Live Trees. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 99, 211-217.

Smith, S.M., Beattie, A.J., Kent, D.S., & Stow, A.J. (2009) Ploidy of the eusocial beetle Austroplatypus incompertus (Schedl) (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) and implications for the evolution of eusociality. Insectes Sociaux, 56, 285-288.